Are the arts in trouble? Not if we take a 360 degree perspective

The apparent decline of the arts subjects in many schools across the country appears to be an unintended consequence of the coalition government’s decision to champion a more overtly academic regime, with its related reforms to the exam system. With hindsight, this decline does not seem so remarkable, perhaps, particularly in the light of the dissolution of local authority control in favour of independent academies and multi-academy trusts, and the consequent loss of long-established networks of advisory specialists. Furthermore, according to a new report funded by the Nuffield Foundation, faced with the inspectorate’s (Ofsted’s) focus on national test outcomes as the key measure of school success, headteachers have been forced to react restrictively to avoid the disastrous impacts that failure on these metrics can have on pupil and staff recruitment, as well as the wider reputation of their schools (1).

The narrowing of the curriculum that has been the result of all this has only relatively recently been recognised as a potentially damaging trend in economic terms. The creative industries contribute in excess of £90bn to our GDP and account for 1 in 11 jobs. These numbers have been rising at a rate faster than all other parts of the economy in the recent past, reliant to a large extent on immigrant talent attracted to our creative hubs. However, the danger that a large gap in the supply chain for future employees in these industries might emerge following Brexit is now very real, according to John Kampfner, CEO of the Creative industries federation, with ‘17 defined skills shortages in areas such as animation and special effects’ (2).

As with other independent schools, at Northampton High we have the freedom to consider developments in national education policy through the lens of our own philosophy and educational beliefs. This gives us the option of only gathering up innovations when we think they are beneficial and channeling our approach to structural changes, so that we can focus on the learning experience and help our students to find their own paths without having to compromise the breadth and balance of the choices they can make. We know that this leads to our Sixth Form students leaving us to go on to a striking range of futures beyond the purely academic or scientific, large numbers of them specifically arts related and many more very closely allied.

As befits our aim of helping our pupils come to a 360-degree understanding of what drives and inspires them, we place the arts squarely at the heart of school life and we encourage them to weave a path in and around the more traditionally academic subjects. Hence art, literature, film, music, food, textiles, dance and drama all feature in the day to day lives of the girls, both in curriculum time and in the wider life of the school. To mention but a very few examples from the last 12 months, this has been seen in our work with both an artist and director in residence, a link with the National Leather Collection, national awards for film, textiles and food collaborations with junior school girls, a dance and gymnastics celebration evening and extensive partnerships with humanities, science, maths and arts subjects across the school, including a STEAM extravaganza last month.

Of course, it would be remiss of me not to mention our stunning annual Arts Festival which this year was bigger than ever, in honour of our 140th birthday, including 3 invited authors to suit all age groups (and parents!), a recital of music performances from girls aged 7 to 18 and arguably the most technically accomplished musical ever produced by the school, the Sound of Music. To finish off a fabulous year for the arts, we are refurbishing our Music department over the summer with the theme of female icons in music, practice rooms no longer being known as room 1 or 2, but by the name of an artist or composer, such as Beyoncé or Clara Schumann.

Needless to say, while the arts are flourishing at Northampton High and at other schools like ours, we cannot do it all. I sincerely hope that the wake-up call to government does not come too late to avoid our national influence in this vital sector being reduced beyond all recognition.

- Toby Greany and Rob Higham, UCL Institute of Education. Hierarchy, Markets, and Networks: analysing the self-improving school-led system agenda in England and the implications for leadership, Nuffield Foundation and IOE Press, July 2018

- John Kampfner. Creative industries are key to UK economy, the Guardian, January 2017

Mr Rickman, Deputy Head Academic

Universities have long complained about the lack of academic independence which many of their new under graduates exhibit. Research into this area has found that many new students struggle to write essays, carry out independent research and build arguments; a lack of skills which leaves them ill equipped for the rigorous academic approach required in higher education.

Universities have long complained about the lack of academic independence which many of their new under graduates exhibit. Research into this area has found that many new students struggle to write essays, carry out independent research and build arguments; a lack of skills which leaves them ill equipped for the rigorous academic approach required in higher education. According to the World Economic Forum, it could take 217 years for the disparities in pay and employment opportunities for males and females to end. In sport, despite the successes of our female sports women on the international stage, there is still a veritable gulf between men’s and women’s sport in a range of areas. In the context of professional football, the highest paid English female footballer Steph Houghton earns £65,000 a year whilst Wayne Rooney earns £300,000 a week. Will this be a gap in professional sport that could ever be closed, or even should it be?

According to the World Economic Forum, it could take 217 years for the disparities in pay and employment opportunities for males and females to end. In sport, despite the successes of our female sports women on the international stage, there is still a veritable gulf between men’s and women’s sport in a range of areas. In the context of professional football, the highest paid English female footballer Steph Houghton earns £65,000 a year whilst Wayne Rooney earns £300,000 a week. Will this be a gap in professional sport that could ever be closed, or even should it be? Confidence is a highly desirable attribute, in life and in learning. The magnetic illumination we sense around people with confidence is almost physical, while the feeling of being confident is exhilarating and empowering; an unstoppable force where there are no immovable objects.

Confidence is a highly desirable attribute, in life and in learning. The magnetic illumination we sense around people with confidence is almost physical, while the feeling of being confident is exhilarating and empowering; an unstoppable force where there are no immovable objects. Girls under 3 do need to have a higher level of adult supervision and support whilst learning to be independent but the requirements of space remain the same. Happiness comes through from our environment but also the types of activities which should be stimulating and challenging, ensuring that well-rounded progress is made. Nursery age girls most definitely require a different experience to boys of the same age. Girls crave structure and routines, where boundaries are clear and expectations high. I am frequently asked about the suitability of girls only at the nursery age and can answer the question simply by giving a tour. Seeing the learning, both direct and indirect, in our setting along with the standards of behaviour and positive friendships is often sufficient to answer the question for me.

Girls under 3 do need to have a higher level of adult supervision and support whilst learning to be independent but the requirements of space remain the same. Happiness comes through from our environment but also the types of activities which should be stimulating and challenging, ensuring that well-rounded progress is made. Nursery age girls most definitely require a different experience to boys of the same age. Girls crave structure and routines, where boundaries are clear and expectations high. I am frequently asked about the suitability of girls only at the nursery age and can answer the question simply by giving a tour. Seeing the learning, both direct and indirect, in our setting along with the standards of behaviour and positive friendships is often sufficient to answer the question for me. Vegetation in the classroom is an idea that we are currently investigating in the light of a GDST research project into CO2 levels and classroom productivity. Some of my favourite classrooms as a child were the ones with huge pot plants that generated interesting smells and shadows. They also help to replenish the air with oxygen, an ingredient which can often be taken for granted in the classroom. We are preparing to install some CO2 monitors in our classrooms to monitor the levels and make sure that a window is opened whenever we reach the cut-off and girls begin to lose their focus. I am sure we will also see classes popping outside for a quick-fire exercise session to reinvigorate and boost those O2 levels in preparation for more hard work.

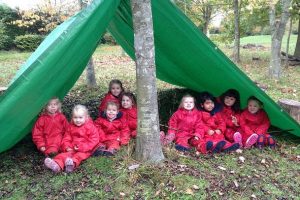

Vegetation in the classroom is an idea that we are currently investigating in the light of a GDST research project into CO2 levels and classroom productivity. Some of my favourite classrooms as a child were the ones with huge pot plants that generated interesting smells and shadows. They also help to replenish the air with oxygen, an ingredient which can often be taken for granted in the classroom. We are preparing to install some CO2 monitors in our classrooms to monitor the levels and make sure that a window is opened whenever we reach the cut-off and girls begin to lose their focus. I am sure we will also see classes popping outside for a quick-fire exercise session to reinvigorate and boost those O2 levels in preparation for more hard work. Many of our girls would argue that the perfect learning environment is actually in our Forest School, and I find it hard to disagree. I am always amazed by the work that takes place ‘at the end of the field’, across the full range of curriculum areas. The elements never seem to get in the way as the tarpaulin shelter is rapidly put up. We hope to make this an even more comfortable space when the clouds darken by installing a permanent shelter to go with the composting toilet!

Many of our girls would argue that the perfect learning environment is actually in our Forest School, and I find it hard to disagree. I am always amazed by the work that takes place ‘at the end of the field’, across the full range of curriculum areas. The elements never seem to get in the way as the tarpaulin shelter is rapidly put up. We hope to make this an even more comfortable space when the clouds darken by installing a permanent shelter to go with the composting toilet!